I recently noticed that the London Metropolitan Archives has launched a new database – Switching the Lens – Rediscovering Londoners of African, Caribbean, Asian and Indigenous Heritage, 1561 to 1840. This is an aspect of history that captured my imagination some time ago [ see, for instance, Suffrage Stories: Black And Minority Ethnic Women: Is There A ‘Hidden History’?] and I was interested to see whether this new database would make the uncovering of individual histories any more possible. Through the centuries there have always been some men and women of BAME heritage living in Britain whose lives have, for one reason or another, been recorded in some degree of detail; the great majority, however, have hitherto remained untraceable.

The database has its inherent limitation in that the 2600 names listed are drawn, over a period of nearly three centuries, from Anglican parish registers. As such it deals only with those who were baptised, married or buried in a parish church in the London area. Nevertheless it contains a wealth of information.

Because I was particularly keen to see if information available on Switching the Lens could be amplified by that already held on genealogical sites such as Ancestry and Findmypast, I concentrating on reading entries in the later period covered by the database, running from 1801-1850. Would it be possible to follow up the lives of any of those people on the Switching the Lens database by, for instance, finding them on the census (from 1841) or identifying them on other national registers?

At a first glance the answer, briefly, is probably not. In general, names are too common or the information is too scanty for it to be possible to identify individuals with any certainty in later official registers. But that is only my finding after a cursory scan. It may well be that keen application will bear fruit. And I shall certainly take a closer look.

As a result of my first venture into the database one entry did attract my attention and I have taken pleasure in unravelling a little of the lives thereby revealed.

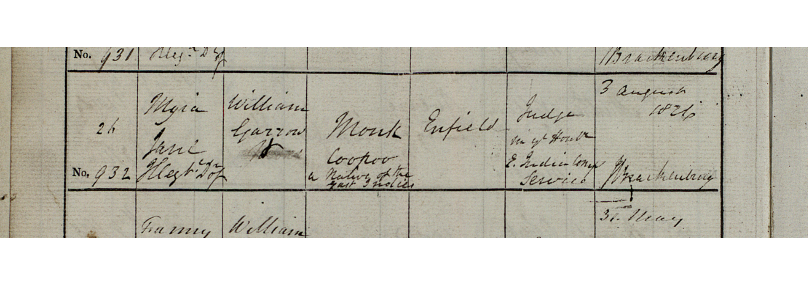

The entry is a baptism that took place on 26 June 1828 at St Pancras Church in the Euston Road, of ‘Miya Jane, illegitimate daughter of William Garrow Monk and Coopoo, a native of the East Indies’. In fact I quickly realised that the girl’s name had been mis-transcribed and she was ‘Myra Jane Monk’, born in India on 3 August 1826. The baptismal register identifies William Garrow Monk (1785-1859) as a ‘Judge’, living in Enfield. Born in Hertfordshire, Monk had been an employee of the East India Company from the age of 20, rising to become a judge in the Madras Presidency. It would seem that he finally returned to England c 1828. If it had not been for the fact that the British Library is closed at the moment I would have enjoyed spending time in the East India Company archive finding our more about William Garrow Monk.

However, the online research that I could do revealed that Myra was not Monk’s only illegitimate child – because William Garrow Monk’s aunt, Elizabeth Monk (d 1832), in her will left money in trust ‘for the benefit of George Monk, Charles Monk and Myra Jane Monk, being the children brought from India by my nephew William Garrow Monk.‘

The inclusion, by name, in their great-aunt’s will, suggests that ‘the children brought from India’ were embraced by the wider family. It is not known whether or not all three children had the same mother, although I would think it right to assume that they did. But of her all that we know is that her surname was Coopoo. We do not know what position she held in Indian society, although it is likely that she was a bibi, living with William Garrow Monk in a marriage in all but name. Nor do we know if she was still alive when her three children sailed for England with their father. There is little possibility that, even if she were still living, she ever saw her children again. In his excellent book, The White Mughals, William Dalrymple relates the fascinating histories of some of the Indian wives and bibis whose lives were intertwined with those of employees of the East India Company.

The names ‘Myra’, ‘George’, and ‘Charles’ were Monk family names – in fact, all three were the names of William Garrow Monk’s siblings. Myra’s second name, ‘Jane’, was that of William Garrow Monk’s mother, born Jane Garrow. The Garrow family had a long association with India. It is notable that neither of the boys was named for their father. As we shall see, that name was reserved for his legitimate first-born son.

George and Charles were older than Myra, but I have not been able to trace entries for them on London baptismal registers. They may have been baptised in India or at an English church, the register of which has not been digitised. The 1891 census does reveal a Charles Monk, born in Madras in 1823, whom I am certain was Myra’s brother. In 1841 he was living in the Chelsea home of a surgeon, apprenticed as a medical assistant. When, now a ‘chemist’, in 1846 at St Paul’s, Deptford, he married, his father’s name is given on the marriage register as ‘William Monk, Gentleman’. However, as William Monk was not one of the witnesses it is impossible to know whether or not he attended the wedding. Charles and his wife had several children and he continued to live in Deptford until his death in 1899. In the 1891 census he is described as ‘retired medical assistant’.

Of George Monk I have been unable to find any convincing trace.

In the year before the death of Great-Aunt Eliza, William Garrow Monk had married, on 26 April 1831, Eliza Ann Archer, 20 years old to his 46 She was the daughter of Thomas Archer, principal clerk to the Treasury. Barely three months later. Archer, a widower, married Myra Charlotte Monk, sister to William Garrow Monk.

William Garrow Monk and his wife were to have at least 6 children, the eldest being William, born in 1832. Some time after his birth the family moved to Hersham, Surrey,, to Hersham Lodge, on the south-east side of Hersham Green. It is not known whether Myra and her brothers spent any time living with their father’s new family. In the 1841 census Myra, aged 14, was boarding at a ladies’ school run by a Miss Chownes in Holly Road, Twickenham.

It is unsurprising to discover that, after her schooling ended, Myra earned her living as a governess. This was just the employment I had imagined would be her lot and was, therefore, satisfied to find her on the 1851 census with the occupation as ‘governess’, a visitor in a house in Camden Terrace, Peckham. She was still living in the area (in Camberwell New Road) in the following year (1 July 1852) when she married Arthur Turley in the church of St Giles, Camberwell, Arthur, living in nearby Champion Grove, was described as a ‘brewer’, although he later worked, perhaps not very successfully, as an architect and surveyor. Myra admits to no occupation. Interestingly the box on the marriage register for her father’s name has no writing – merely a line through it – although in the ‘Occupation’ column he is described as ‘Gentleman’ However her father was there in the church, signing himself ‘W.G. Monk’ as one of the witnesses. I was ridiculously pleased to know that this father appears in no way to have rejected his illegitimate, half-Indian, daughter.

Arthur Turley was originally from Yorkshire and after their marriage the couple moved north to Bradford where the eldest of their seven children was born in 1854. Their family eventually comprised four daughters and three sons. Arthur’s business appears to have been precarious and certainly in 1870, when they were living in Sowerby Bridge, Myra was supplementing their income by running a school, presumably in their house. A year later the 1871 census shows that the family had moved to Halifax and the older three children were already in employment. Myra, the eldest (17), was a weaver, Evelyn (15) a boot stitcher, and Arthur (12) a telegraph messenger boy.

By this time Myra’s father, William Monk, had been dead for 12 years and I wondered how his legitimate family was faring without him. He had left under £1000 and by 1861, two years after his death, Eliza, his widow, and three of her now adult children had moved to a Brixton villa, The sons were all then described as ‘unemployed’ but by 1871 one was a stockbroker and his brother and sister were both ‘music professors’. The fact that the daughter, Mary, had an employment perhaps indicates a degree of financial necessity and makes her class position not much different from that of her illegitimate half-sister, who worked occasionally as a teacher. Nevertheless Mary’s life was made more comfortable for her by the cook and housemaid whom her mother was able to employ. Myra had no live-in help.

After Arthur Turley’s death, Myra, now living in Leeds, once more became a schoolmistress, the 1881 census showing that two of her daughters were also now teachers. It is probable that she had again resorted to setting up a school in her home, with two of her daughters, Evelyne and Agnes, to help her. In the next census, in 1891, still living in Leeds but with only Evelyne now at home, Myra is described as a ‘boarding-house keeper’. Her one boarder is, however, a professor at the Yorkshire College (later University of Leeds) so one imagines she ran a house that had a slight social cachet. Her eldest son, Arthur, followed in his father’s footsteps as a land surveyor, eventually achieving the position of surveyor to the city of Canterbury.

Three of Myra’s daughters, Myra, Evelyne and Laura, married and emigrated to the USA, although Evelyne and Laura returned eventually to live in north Wales. The US census in the early 20th century took note of race/colour and, interestingly, in all the censuses in which they feature the grand-daughters of Coopoo are classified as ‘white’.

I have found a photograph of Laura Garrow Cullmann (nee Turley), taken, with her husband, in 1920, nearly 100 years after the birth of her grandmother in India.

I am not sure if this brief research tells anything other than an interesting story. But it would seem to me that, looking from the outside, being both illegitimate and mixed race caused Myra Jane Monk (1826-1915) no specific difficulties in 19th-century Britain. One can never, of course, know what the circumstances of her birth meant to her. That would be a story I would very much like to hear.

Copyright

[1871 census has her as born 1830 in the East Indies

1881 census born c 1827 British India – widow, schoolmistress, living in Leeds. 3 daughters are teachers]

Myra Jane Monk – full age – of Camberwell New Road, m Arthur Turley, brewer of Champion Grove on 1 July 1852 at St Giles, Camberwell. He gave his father as William Turley, commission agent – but she left her father’s name blank, but gave his rank as ‘Gentleman’

One of the witnesses to the marriage was W.G. Monk. I am sure this is her father, William Garrow Monk.

1832 William Garrow Monk (1785-1859) m Eliza Archer (a minor) at St George, Hanover Sq. He was son of William Monk and Jane Garrow, nephew of Sir William Garrow, eminent lawyer

6 May 1853 birth of son William Arthur Turley, North Parade, Bradford

Several children. One, Laura, given Garrow as a middle name

One of daughters, evelyn, emigrated to us in 1893 and was classed as white in 1905 census

Died 1915

But in fact she was only one of the 3 children brought home from India by WW monk. In g monk’s aunt’s will, Elizabeth monk in 1832, she left 600 pounds ? In trust fund for them. George and charles